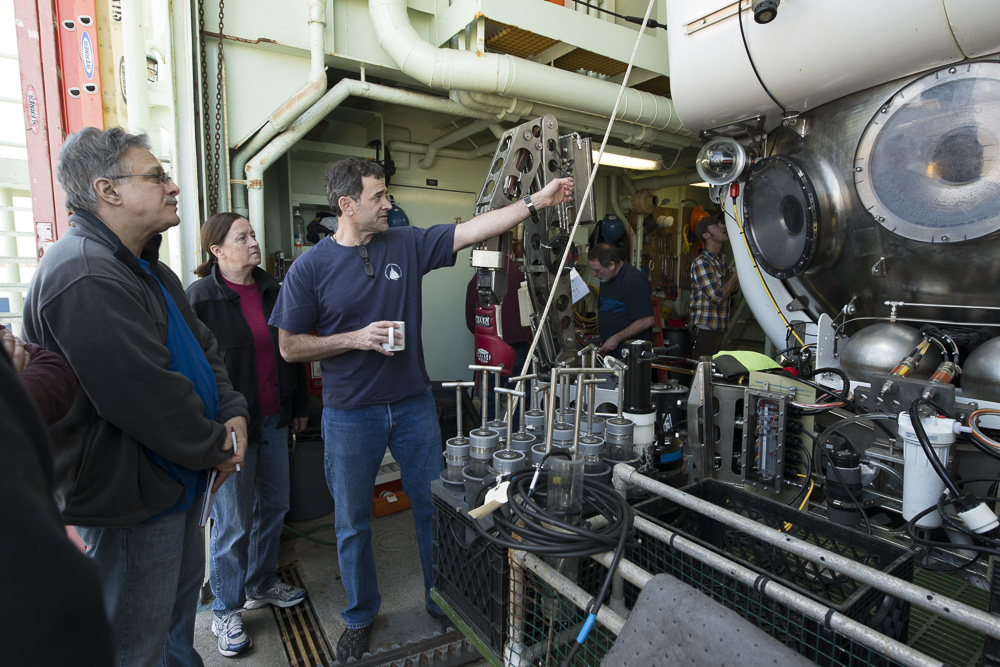

Nearly 900 days since its last research dive—and the most extensive upgrade in its nearly 50-year history—the submersible Alvin is scheduled to return to the depths this morning on a science mission. Everyone on board the R/V Atlantis, from scientists to pilots to ship’s crew, is abuzz and eager to launch the new, improved sub.

In the sub will be veteran Alvin pilot Bob Waters and Susan Humphris, a marine geochemist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Humphris has more than 30 dives in the sub and was the lead scientist responsible for completion of the upgrade.

“Susan is the scientist who is most intimately familiar with what the sub can do and soon to be the most intimately familiar with what it will do,” said Pete Girguis of Harvard University, chief scientist on the research cruise.

The third passenger will be Nate Brown, a pilot-in-training. For him, this dive will be doubly historic: Alvin‘s 4,679th dive will be his first.

The site chosen for the first dive is called Viosca Knoll (VK) 862. “It’s an area of fantastic deep-sea coral communities,” said Amanda Demopoulos, a research scientist at the U.S. Geological Survey who has studied the site.

This area on the continental shelf of the Gulf of Mexico has mounds of carbonate rock that provide hard surfaces for the corals to colonize. The coral colonies that grow here range in color from white to salmon to red. Many are large, slow-growing, and long-lived. Black corals (Leiopathes spp.) collected from this area have been estimated to be more than 2,000 years old, based on age estimates from Demopoulos’ USGS colleague, Nancy Prouty.

But corals are not the primary goal of this dive. VK 862 is also shallow, only 312 meters (less than 1,000 feet). Typical Alvin dives go far deeper and take 90 minutes to two hours for the sub to reach the seafloor. Here, it will only take 15 to 20 minutes for Alvin to descend to the site, and the same to return to the surface. That leaves more time at the bottom for Waters, Humphris, and Brown to test a dramatically reconfigured and rebuilt sub.

They will evaluate Alvin‘s attitude—how level it sits when it is neutrally buoyant at depth. They will check its propulsion system, which includes a new lateral thruster, and assess its ability to respond to commands to maneuver carefully around obstacles or hold position while taking a sample around pristine and delicate ecosystems. They will experiment with the new Alvin‘s more flexible manipulator arms in concert with its two new forward-facing viewports, which allow pilots and observers to look at the same thing simultaneously. They will also perform more basic operations, including driving a straight line across an area of flat, relatively featureless seafloor to assess the new sub’s transit speed between sites of interest that may, at other locations, be a mile or more apart, and how much energy it uses in the process. If time permits, they will also visit coral sites to test how best to configure the sub’s improved lighting and HD camera systems.

“This being a new vehicle, there are bound to be hiccups,” said Humphris. “But that is why we are out here—to test the systems and figure out what needs changing.”

That’s a good day’s work, and by the end of the day, we’ll get our initial glimpse of how the new Alvin fared in the water.