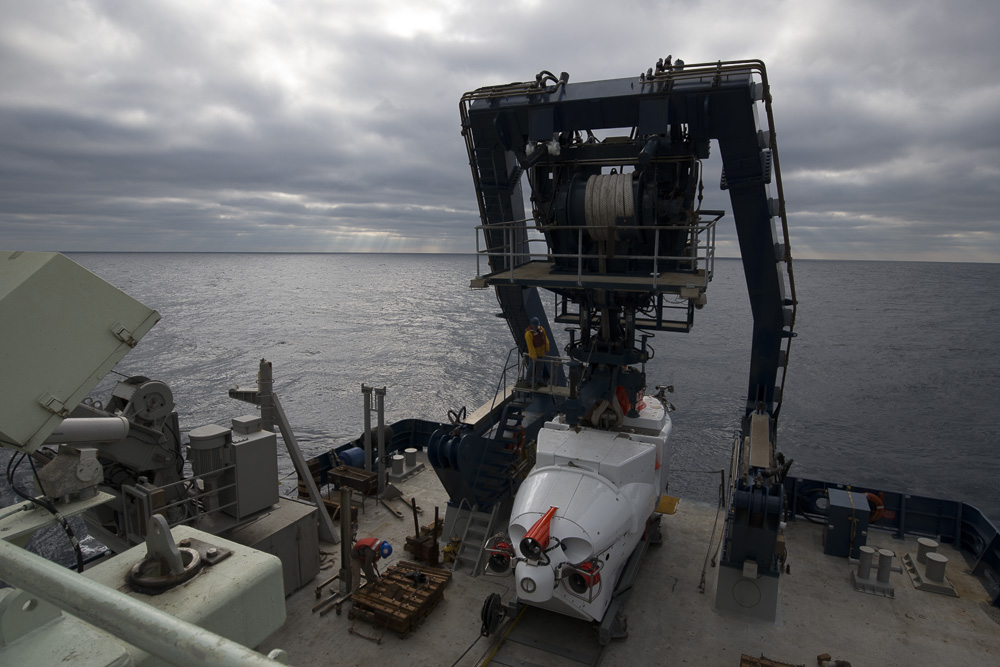

After a decade of planning, designing, engineering, and construction, an upgraded Alvin has been delivered to the nation’s scientific community.

“So then what? What do you do? Brand-new submarine, fresh off the lot,” said Peter Girguis, chair of the Deep Submergence Science Committee (DESSC), a group of scientists that advises on the best use and operations of the sub.

“You can send it straight into service,” he said, which is path that’s routinely taken with new remotely operated or autonomous underwater vehicles. On the other hand, a sub that has been on extended hiatus and significantly rebuilt is likely to return with a few bugs that won’t necessarily compromise its safety, but could still prove cumbersome to the first scientists using it for research.

That’s why scientists from DESSC and the National Deep Submergence Facility at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), which operates Alvin for the scientific community, agreed on a different approach in this case. With support from the National Science Foundation, they organized an expedition with veteran Alvin users and early-career scientists from an array of scientific disciplines and institutions. Their mission: to test the vehicle, assess its capabilities, figure out how best to use its new features, and work out any bugs in order to make Alvin‘s transfer back to science operations more seamless.

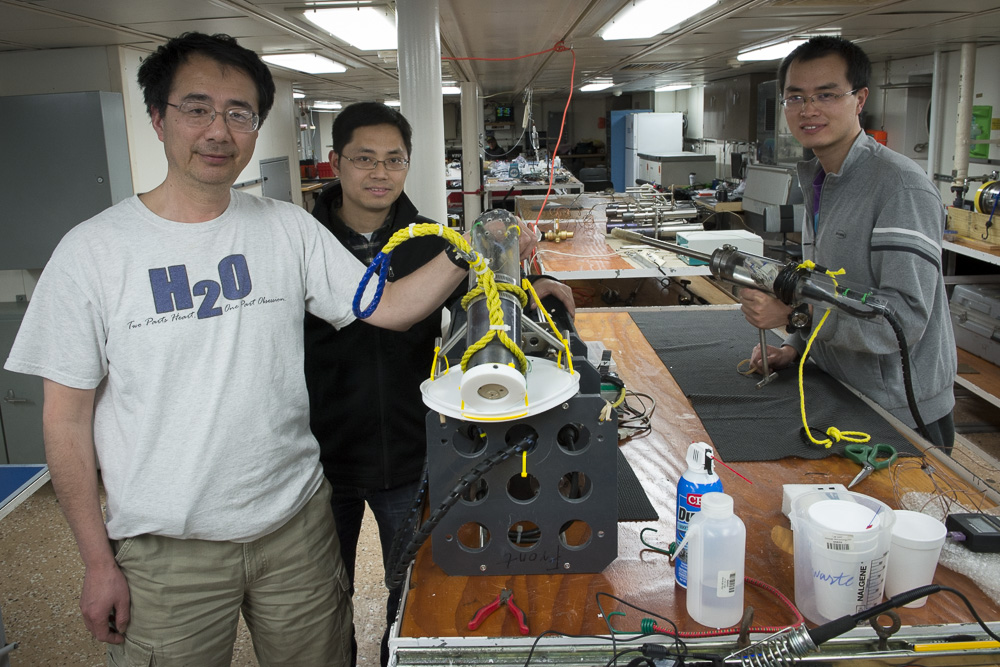

One of those scientists is Kang Ding of the University of Minnesota, who has long used Alvin to test instruments that his lab custom-builds to take measurements at the bottom of the ocean. On this voyage, he brought along the latest model of a wand-like device that measures pH and water temperatures as high as 400°C at hydrothermal vents. It also sniffs out chemicals such as hydrogen sulfide and evidence of chemical reactions that are telltale indicators of bacteria and other microorganisms living at the bottom of the ocean.

The device is nicknamed the “Ghostbuster” (for reasons you’ll see in today’s slideshow). This latest version, the “Super-Cali-Ghostbuster,” is self-calibrating, which allows it to make much more reliable readings, especially in such a harsh environment.

A main objective of Monday’s dive was to see how the new Alvin interfaces with the sorts of instruments scientists would want to plug into it and control or monitor from the personnel sphere in order to make decisions on the fly about where to go in order to take more measurements or gather samples. Ding’s instrument offered a good preview of how the process will work.

Although he has used instruments on Alvin many times in recent years, he still marvels at how challenging it is. “In a room, you plug your instrument into a computer,” he said. “But now put that instrument in water under pressure so high the water tries so hard to get into your plug. If one drop of water gets in, your instrument fails. The connections have to be perfect.

“The night before our dive, our instrument worked on the bench, but when we connected it to Alvin, there was a water leak, and we got a short. We worked until past 11:00 p.m. to search for where the problem was and correct it. The Alvin Group has experience to help ensure that your instruments will work.”

Ding and WHOI geochemist Chris German dove in Alvin Monday to a “cold seep” site 1,095 meters deep, where life-sustaining chemicals percolate up from seafloor sediments. Microbes harvest energy from these chemicals and use it to convert inorganic forms of carbon into organic forms—just the way plants and photosynthetic bacteria use light energy to convert carbon dioxide and water into sugars.

The sub rode up over a knoll, following a trail of clams and a few telltale rocks on an otherwise muddy seafloor. Atop the knoll was a depression in which a fish hovered. White rocks on the rim of the hole betrayed signs of gas hydrates—natural gas made solid by the cold temperatures and high pressures of the deep.

But looks can be deceiving. So pilot Bruce Strickrott used one of Alvin‘s manipulator arms to position the wand of the Super-Cali-Ghostbuster above the hole for 30 seconds. Readings from the instrument soon showed the scientists in the sphere that there was a chemical imbalance in the vicinity.

Most likely this was caused by methane percolating up through sediments at the seafloor. Within the pore space between sediment grains, the methane reacts with sulfate dissolved everywhere in the oceans to form hydrogen sulfide, among other things. These microbes nourish the clams that initially caught the scientists’ eyes, as well as many other organisms.

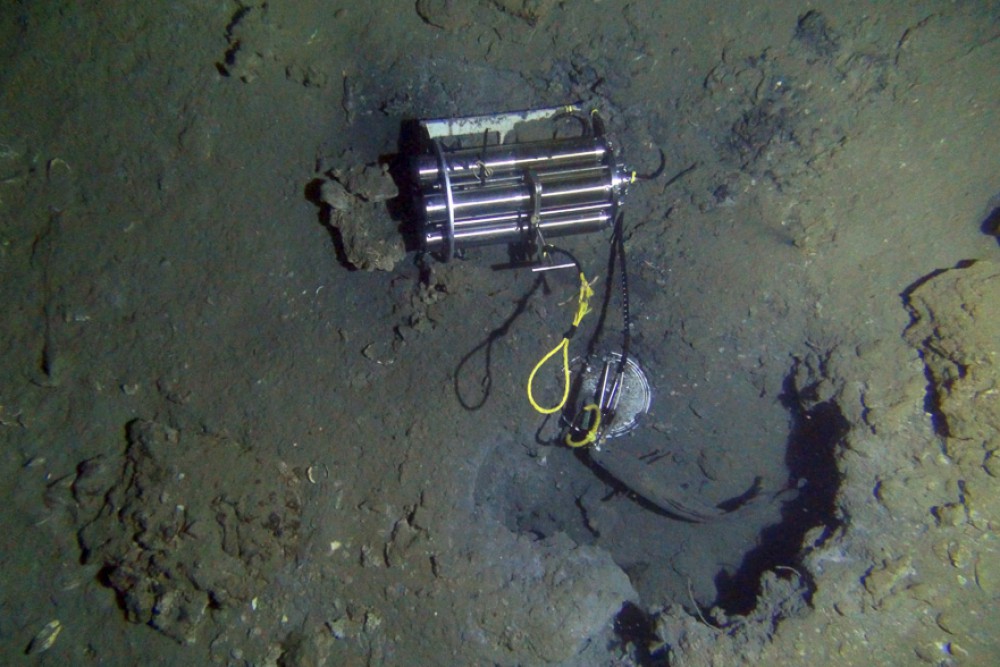

Based on the readings, they decided the spot was ideal for another instrument that Ding brought down on Alvin nicknamed the “six-shooter.” It measures temperature and is designed to take water samples every six hours so that scientists can determine whether seawater chemistry in the deep ocean changes over the course of a day. Ding’s experiment is designed to test whether tidal changes circulate water around chemosynthetic sites at the seafloor, just as they do in coastal ecosystems every day.

Ding sees promise in this sequential approach: Scientists looking in Alvin see a good location to take measurements. Then they use precision sensors to get real-time measurements. Based on that data, they make decisions on where to conduct further experiments.

“This is the way to fully utilize the sub,” he said.