Since its birth in 1964, the deep-sea research submersible Alvin has been brought in every few years for overhauls. Most were routine maintenance—the submarine equivalent of a 30,000-mile servicing on your car.

Some overhauls, however, were more substantial, resulting in improvements and incorporating new technology that permitted Alvin to evolve over time. As a result, the sub that was christened a half-century ago looked very different than the one that investigated impacts from the Deepwater Horizon disaster in the Gulf of Mexico in December 2010.

Alvin in its hangar waiting for tomorrow’s departure. (Photo by Chris Linder, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

After that mission, Alvin was brought to Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) for a scheduled overhaul. But this one was nothing like all the rest. The community of ocean scientists had petitioned the National Science Foundation (NSF) to consider something more ambitious, something that would allow scientists to use the sub to push the boundaries of deep-sea exploration for years to come.

As in every previous overhaul, engineers at WHOI completely dismantled Alvin, and the sub they reassembled bears the same name as the one that arrived on a cold December day 28 months earlier. But so does a 2014 Cadillac and the one your grandfather owned.

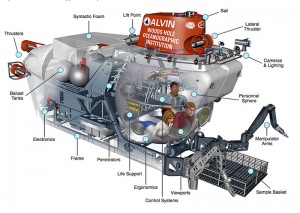

The upgrade began with the forging of a new titanium personnel sphere designed to eventually take passengers to depths of 6,500 meters and reach 98 percent of the seafloor. The diameter of the new sphere is 6.5, rather than 6, feet, an expansion that provides 18 percent more interior space and offered room to include such creature comforts such as benches for observers to sit or lie on, instead of having to scrunch with legs intertwined on the sparse floor of the sphere.

The sphere also has five rather than three viewports, with three of them larger than before. The three forward viewports have also been strategically placed so that scientists and the pilot can see the same thing at the same time. That may not seem like such a big thing, but in the old Alvin, the viewports were so far apart that scientists directing a pilot to grab a specific rock or clam could see it through their own viewport, but the pilot could not, or vice versa.

To further enhance sampling capabilities, the shoulder joints in Alvin’s manipulator arms were given more flexibility, expanding the arms’ reach, and the sub’s basket was enlarged to carry more payload to the bottom—and more samples back to the surface.

The upgrade hardly stopped there. You can explore more about Alvin‘s upgraded features here. Briefly, they include:

• New syntactic foam to provide buoyancy

• A new lateral thruster to improve maneuverability

• A new command-and-control system to enhance the sub’s ability to maintain a position.

• A new electronics system, incorporating fiber-optic cables for the first time on Alvin to greatly increase bandwidth for data collection

• New LED lighting and high-definition cameras

In November 2013, Alvin completed a series of certification dives in the Pacific, and in January it received clearance from the U.S. Navy, the sub’s owner, to return to service initially to depths of 3,800 meters. But certification of seaworthiness is only one step on the path to delivery of a fully functional research submarine.

Peter Girguis, chair of the Deep Submergence Science Committee (DESSC), the group of scientists that advises on the use of vehicles operated by the National Deep Submergence Facility at WHOI, organized this verification cruise aboard the research vessel Atlantis and brought aboard veteran scientists who have used the old Alvin many times before as well as early-career scientists who will use the new sub in the future. “It became apparent to the broad scientific community that the Alvin upgrade project is functionally equivalent to deploying a new vehicle, and we don’t have a sense of this sub’s performance yet,” said Girguis.

More than three years after its last research mission, Alvin returns to the scene of its last scientific dive, the Gulf of Mexico, nothing like its old self. During the cruise, scientists and pilots will take the new sub through its paces in a series of dives, conducting a variety of increasingly complex scientific operations under real field conditions. They will assess its capabilities, learn what the sub can do and how to use it to best advantage, and they will identify any hiccups to be remedied or items that could be improved.

For the geeks among you, here is a list of critical capabilities that scientists, engineers, and pilots aim to test on this voyage:

• Navigation, maneuverability, and data collection on the seafloor and in the water column,

• Power, speed, and duration during observations and in transit between work areas

• Coverage and quality of lighting and imaging systems, as well as ease-of-use of recording, output, and archiving systems

• Flexibility and capability of various instruments and sampling configurations on the seafloor and in the water column, including the use of both manipulator arms for fine-scale sampling and instrument manipulation

• Ability to manipulate and interface with user-provided equipment in the sample basket or on the seafloor and to interact with elevators

• Passenger/pilot comfort and ability to interact with each other while using viewports, cameras, controls, and recording devices

• Ease of mobilization and demobilization before and after dives

• Simulated interactions with seafloor observatory and IODP infrastructure

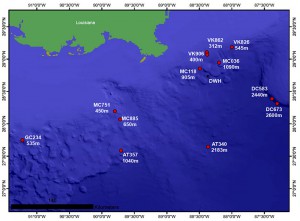

The location for this Science Verification Cruise (SVC) was chosen for the diversity of features, bottom types, species, and habitats that are spread across a relatively confined area. The planned dive sites include:

• VK862: A coral site with abundant grouper and anemone that will also be the site of midwater assessments.

• MC118: This well mapped site is a focus of the Gulf of Mexico Hydrates Research Consortium (GOM-HRC) and presents an interesting geophysical setting, as well as seeps, corals, mussels, and tubeworms.

• AT357: A large deep-water coral site that has already been well-mapped.

• AT340: A large, diverse seep site with mussels, clams, and tubeworms as well as a Chemo III site, which has been well studied by Chuck Fisher of Penn State University, a member of the assessment team.

• MC036: A site near the source of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2010 that may allow exploration and sampling of seafloor habitat that may have suffered impacts from the spill.

• DC673: A location on the northern extent of the Florida Escarpment that has several cold seep sites along the base and along a coral wall above.

With departure set for 8:30 a.m. tomorrow (Friday), Susan Humphris, the WHOI scientist who oversaw the upgrade, summed up the mood on R/V Atlantis tonight. “After three and a half years and a lot of hard work from so many people, we’re excited to see Alvin get back in the water and to test all of its new components.”