On the morning he was scheduled to dive in Alvin, Adam Soule slept soundly. So soundly, in fact, that he slept through his alarm. The Alvin Group and the ship’s crew were just about finished preparing for Friday’s dive when Soule’s roommate aboard the research vessel Atlantis, Jeff Marlow, roused him so he could make his appointment to go to the bottom of the ocean.

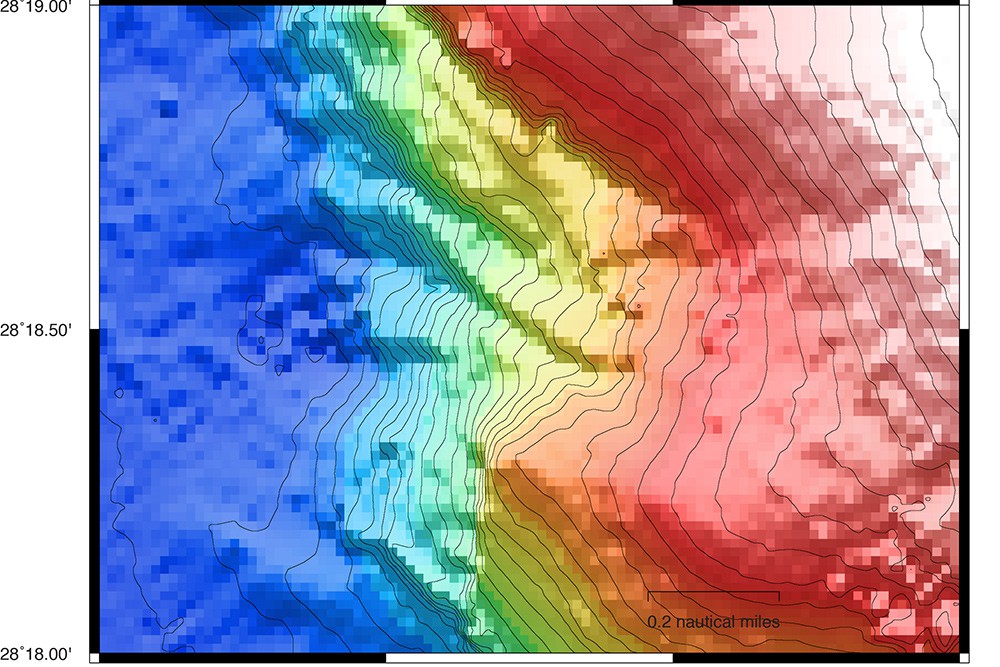

Two nights before, Soule, a marine geologist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), had stayed up all night, strumming his ukulele while minding the ship’s multibeam sonar. It was creating a map of the area that Soule would dive on: the Florida Escarpment.

Located off Florida’s West Coast, it is a large, stepped, rocky platform made of long-dead corals, mollusks, fish skeletons, and other organic matter that have accumulated over geological time. Through cracks and fissures in the carbonate bulwark, groundwater that has percolated through Florida seeps into the sea.

This water is full of chemicals, particularly hydrogen sulfide, that nourish microbes. Many of the microbes are endosymbionts, living inside larger animals such as mussels, clams, and tubeworms. The animals give the microbes safe haven and a constant supply of chemical-rich fluids; in exchange, the microbes turn the chemicals into food for the animals.

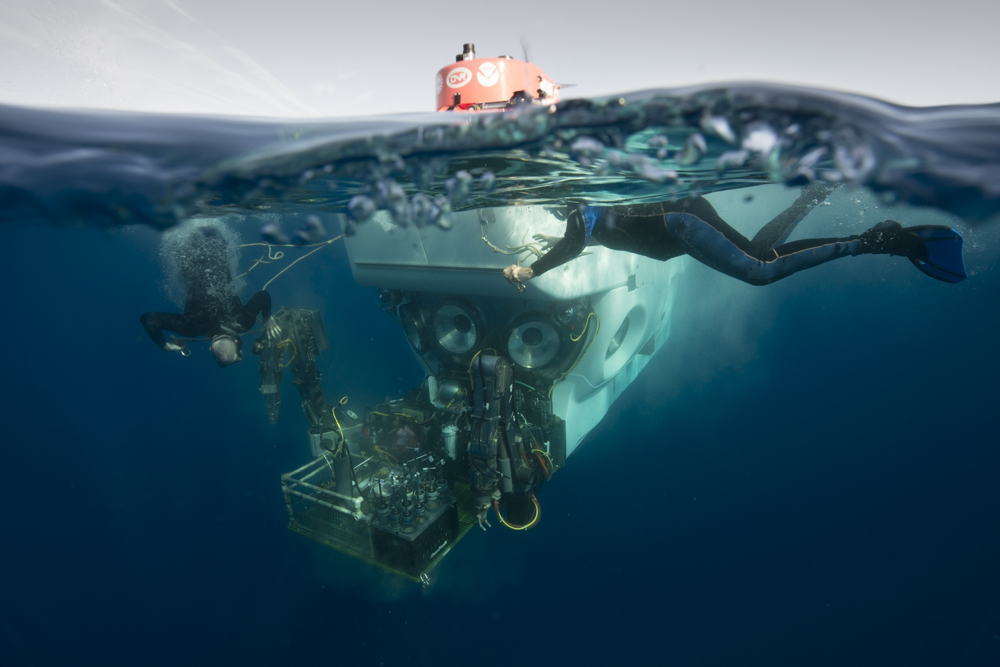

The site was 2,610 meters (1.6 miles) below the sea surface, more than twice as deep as previous dives on this research cruise and as deep as any of the three upcoming Alvin science expeditions are likely to go. It was an excellent place to continue testing core features of the rebuilt Alvin.

“We’re moving at deliberate speed, making sure the core attributes of the rebuilt Alvin are functioning well,” said Harvard University scientist Peter Girguis, the expedition’s chief scientist.

At the surface on Atlantis, WHOI engineers Jonathan Howland and Scott McCue canceled their plans to depart Saturday on a mid-cruise at-sea transfer of scientists, so that they can continue troubleshooting the data gaps in the video stream from the sub’s cameras. They hope to iron them out before the cruise ends next Wednesday.

Meanwhile, at the base of the escarpment, Soule, Pilot Pat Hickey, and Pilot-in-training Chris Lathan explored the upper limits of the new Alvin’s Doppler Velocity Log. It is a key component that measures the sub’s speed by measuring Doppler frequency shifts of sound transmitted and reflected off the seafloor. It worked to an altitude of 80 meters (about 260 feet) above the seafloor, Soule said.

Though a veteran of more than 600 Alvin dives, even Hickey didn’t have significant experience with some of Alvin’s new or modified features. The sub’s new lateral thruster, for example, allows the sub to move sideways more efficiently, so that it can move along an escarpment while facing it head-on. The shoulder joints on the sub’s manipulator arms are more flexible, extending their forward reach from 93 to 118 inches (2.3 to 3 meters) and expanding their coverage area from about 100 to 140 degrees.

The pilots used the manipulator arms to extract 12 cores of seafloor sediments, then used them to grab and scoop specimens of tubeworms and mussels that lined a tall crack in the rock face that spewed life-sustaining, chemical-rich water. They took chemical and temperature measurements of the fluids with a probe brought on the expedition by University of Minnesota scientist Kang Ding. And they collected more video data to see how modifications made the night before to the sub’s lighting system might improve the video’s quality. (Stay tuned.)

And every dive is a test of the new Alvin’s larger sphere with padded benches.

“It’s comfortable,” Soule said, “but I didn’t mind the old sub. I mean, you’re at the bottom of the ocean. You can throw comfort out the window.”

Metaphorically, of course. Not in Alvin’s sealed titanium sphere.

It’s fantastic to see Alvin back at work in its natural environment. The rebuild and upgrades presented some unbelievable hurdles for the Alvin crew and WHOI engineers to overcome. I have great admiration for what they achieved and congratulate them for the job well done. As others have mentioned, some teething problems are to be expected, but the crew and engineers all well qualified to sort them out. My best wishes to the Alvin group for providing many more decades of this unique access to the deep sea.